I love broken things, unfinished things, breaking things, unfinishing things. Broken and unfinished things allow you to see the process in which they were created; their most intimate secrets are exposed.

Broken Statues

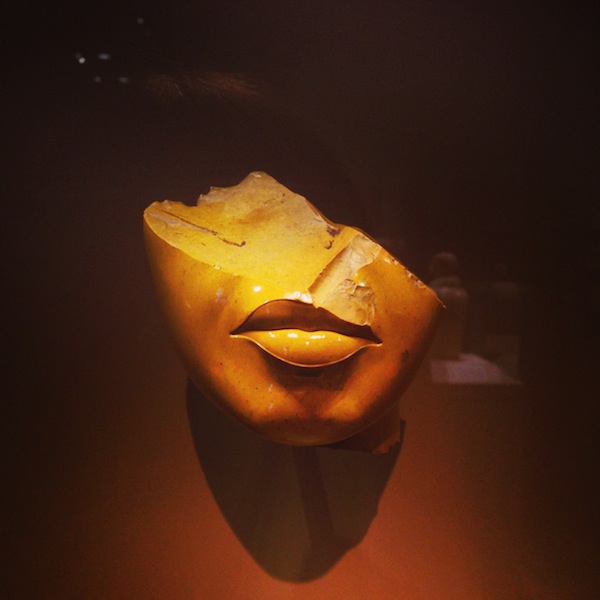

A week ago, inside The Metropolitan Museum of Art, my love for broken things was realized. Just look at these. They're so naked, vulnerable.

Okay so some of them are literally naked, but you get the point. When a statue is broken, you can sneak a peek inside! You get so many clues about how it was made! Is it hollow? What's it made out of? Is the material on the outside the same as the inside? Does it have a frame?

Breaking Code

While I can't bring myself to break art to get clues about the process of its creation, I can break code! Breaking code is free and doesn't hurt anyone! (As long as you keep it local...) I do this quite a bit as a method of learning - removing the pieces of code that you don't understand reveals the purpose of those pieces. It's like removing the arm of a statue to look inside.

Let's look at some code from Mary Rose Cook's functional programming tutorial (which is amazing, and you should absolutely read it and do the exercises and spend time understanding it completely if you're at all interested in functional programming). We won't understand the code at first (or at least I won't), but we'll take apart the pieces of the code in an attempt to better understand their purpose.

Mary aptly explains what Python's builtin map function does:

Map takes a function and a collection of items. It makes a new, empty collection, runs the function on each item in the original collection and inserts each return value into the new collection. It returns the new collection.

Her first example for showing how map works is fairly straightforward:

This is a simple map that takes a list of names and returns a list of the lengths of those names:

name_lengths = map(len, ["Mary", "Isla", "Sam"]) print name_lengths # => [4, 4, 3]

In the second example of map, we see that Mary uses a lambda function:

This is a map that squares every number in the passed collection:

squares = map(lambda x: x * x, [0, 1, 2, 3, 4]) print squares # => [0, 1, 4, 9, 16]This map doesn’t take a named function. It takes an anonymous, inlined function defined with lambda. The parameters of the lambda are defined to the left of the colon. The function body is defined to the right of the colon. The result of running the function body is (implicitly) returned.

But why does Mary use a lambda function here? Let's spend some time breaking this code and reconstructing it to understand why the lambda function is used.

First let's try removing the lambda and seeing what happens:

>>> squares = map(x * x, [0, 1, 2, 3, 4])

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

NameError: name 'x' is not defined

Okay. x is not defined. That makes sense, because x isn't in our locals or our globals or our builtins. Remember that when Python sees the name of a variable, it looks in those three places for a definition of that variable. If Python doesn't find the variable in any of those places, it throws a NameError. lambda must temporarily add variables (here, x) to our namespace and then throw them away.

We removed the arm of the statue and a NameError was revealed. Cool. Now let's try naively reconstructing the statue.

What if we tried using the ** operator? Can we pass something like **2 as the function for map? Let's try:

>>> squares = map(**2, [0, 1, 2, 3, 4])

File "<stdin>", line 1

squares = map(**2, [0, 1, 2, 3, 4])

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

This SyntaxError makes me think that ** is part of a statement, defined in Python's Grammar file, and the way that we typed our code is in violation of the the definition of that statement.

I am going to cheat a bit here. I am going to present something I found on the internet that helps us understand this SyntaxError without showing how I knew what to google to get the answer. At some point I'll write about, given a SyntaxError, how we can find the relevant rules defined in Python's Grammar, understand which rules we're violating, and adjust our code to obey. But not today.

So the short story is I did some research to figure out how ** Python operators are defined:

power ::= primary ["**" u_expr]

The important thing to note is that any time Python sees ** in this context, it expects a thing called a primary to come before it and a thing called a u_expr to come after it. We can tell we violated this rule without even understanding what a primary or a u_expr is. We tried typing **2, which doesn't include anything that could be interpreted as a primary before the **.

Okay. So we can't reconstruct Mary's function using ** instead of lambda.

What else could we try instead of a lambda function? Is there a function already defined in Python that does the same thing as the operator ** but in function syntax?

Let's google "python power operator function." We quickly discover that there's a builtin pow function that takes two parameters, x and y and returns x**y. Cool! So pow(x,2) should return the same thing as x**2.

Does the pow function work in our map function? Let's try!

>>> squares = map(pow, [0, 1, 2, 3, 4])

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: pow expected at least 2 arguments, got 1

Oh, right. Derp. We need to pass 2 to pow, in addition to each element in our list. In the documentation for map, we see that if the function takes two arguments, we need to pass it two iterables. So we could do something kind of dumb like:

>>> squares = map(pow, [0, 1, 2, 3, 4], [2, 2, 2, 2, 2])

>>> squares

[0, 1, 4, 9, 16]

It works, but it's pretty ugly compared to the original:

>>> squares = map(lambda x: x * x, [0, 1, 2, 3, 4])

It seems silly to use a function, pow, that takes two arguments, when one of the arguments we pass it is always the same.

Ohhh.

Maybe that's why Mary used lambda! To create a function that works kind of like pow but just takes one argument!

So we broke the statue, attempted to reconstruct it, and then wound up with something way uglier than the original. And thus, through breaking Mary's code, her design decisions were revealed! And now we have a better understanding of why the original process was used!

Breaking things is fucking rad.

Disclaimer: This post is not intended to show the most pythonic way of squaring a list of integers. Instead, it is intended to show that we can discover how and why a code block works by exploring what happens when we remove chunks of it.

tags: learning hacker school python functional programming map lambda python internals grammar

Comments